New data on the profitability of Argentina’s largest corporations help explain the origins of its last military dictatorship.

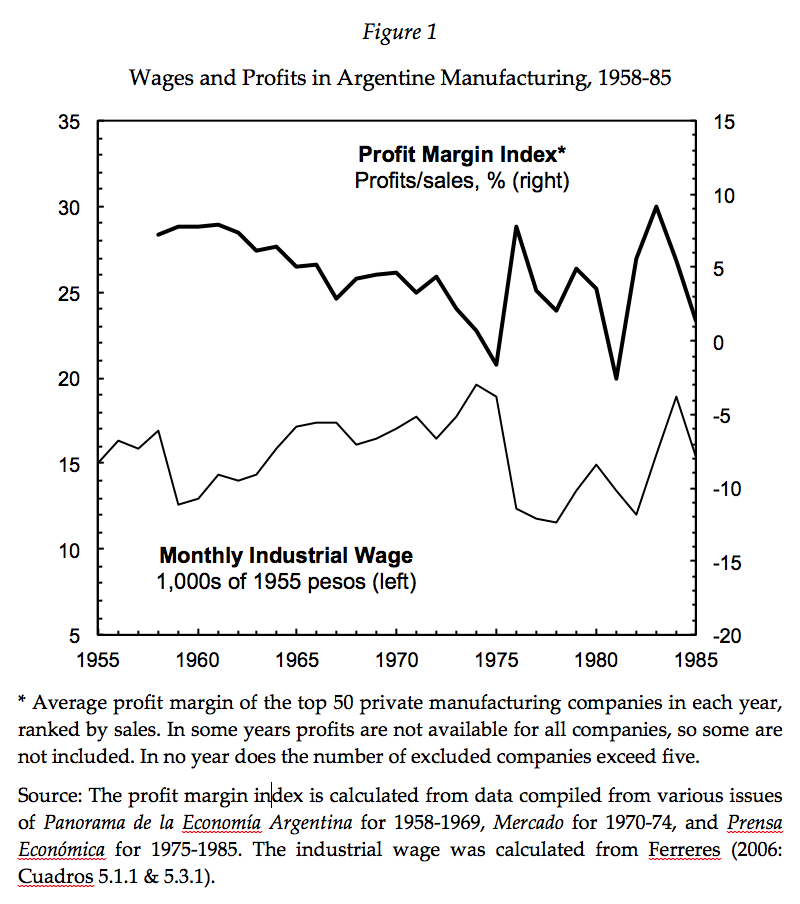

During Argentina’s military dictatorship of 1976-1983, up to 30,000 people were killed by the armed forces. Figure 1 provides an indication of why.

The thick line is a ‘profit margin index’ of the fifty largest private manufacturing companies during 1958-1985. These data were compiled from the rankings of Argentina’s largest industrial companies, which have been published in various business magazines since the late 1950s. The average profit margin (that is, profits divided by sales) was then calculated for each of the top fifty companies in each year from 1958 to 1985. The result is an unconventional but simple method of measuring profitability – necessary in this case because there is a lack of data on large corporations’ profits in Argentina.

Until the military coup of 1976, there was a close negative correlation between the profit margin index and real wages. The correlation began in the late 1950s – an era of low wages and high profits, during which numerous transnational corporations established themselves in Argentina. For the next decade and a half, however, wages rose and profits fell during a period of increasingly radical social unrest, characterised by simultaneous and conflicting movements to both democratise society and to establish a ‘corporatist’ order based upon the government’s regulation of the class struggle.1 Both social movements proved disastrous for big business, in that they led to large companies losing control of the prices that they both paid and charged. The result was the profitability crisis shown in Figure 1.

The tendency toward rising wages and falling profit margins was reversed decisively after the military coup of 24th March 1976. On the first anniversary of the coup, the journalist Rodolfo Walsh described how the reversal had been achieved:

In the economic policy of this government we must seek not only the explanation of its crimes but also a greater atrocity that punishes millions of human beings with a planned misery. In one year they reduced workers’ real wages by forty percent, reduced their participation in the national income to thirty percent, increased the working day that is needed to purchase the family basket [of basic goods] from six to eighteen hours, resuscitating forms of forced labour that do not persist even in the last colonial redoubts. Freezing wages with the butt of a gun while prices are increased at the point of the bayonet, abolishing every form of collective bargaining, prohibiting assemblies and internal committees, increasing working hours, raising unemployment to a record ten percent, and promising to increase it even more with 300,000 new redundancies – all of this has brought productive relations back to the beginning of the industrial era. And when workers have wanted to protest they have been called subversives, with the kidnapping of entire groups of unionists, some of whom reappear dead, while others do not reappear at all. (Walsh 1977, my translation) 2

What can be added to Walsh’s analysis is an account of how big business itself participated in solving the profitability crisis. Business participation in state terrorism appears to have been widespread, particularly among larger companies (Andersen 1993: Ch. 12; Basualdo 2006). A report by the US ambassador in June 1978 gives an indication of how prevalent it was. Having described the specific case of the disappearance of dozens of ceramics workers in Buenos Aires Province, the ambassador went on to make the general statement:

We believe there is a great deal of cooperation generally between management representatives and the security agencies aimed at eliminating terrorist infiltrators from the industrial work places and at minimizing the risk of industrial strife. Security authorities have made a general observation to embassy elements recently […] that they are taking greater care than in the past in dealing with denunciations from management of alleged terrorist activities in the plants which may be little more than legitimate (albeit illegal) labor unrest. (Castro 1978: 3)

Furthermore, it can be added that even those companies that did not actively participate in state terrorism still used the atmosphere of fear to fire their most militant workers without fear of retaliation (Munck 1998: 67-68).

Ford Motor Company provides one of the best-documented cases of business participation in the terror. It is also one of the most symbolic because the Ford Falcon was the model of car used by the military’s death squads to kidnap their victims. Witnesses claim that Ford’s subsidiary in Argentina provided the military with a list of workers that it wanted eliminated, providing company files so that they could be identified. A detention centre was then established in the sports field of the company’s factory in Pacheco, where the company’s head of security participated in the torture of detained workers (CONADEP 1984: Part 2.H; Basualdo 2006: 12-13; Hearn 2006). A conscripted soldier would later testify about Ford’s relationship with the military:

The operations would last all day, and we would have lunch at the Ford [factory] in Pacheco. […] Before leaving, the officer in charge would make a kind of motivational speech in which he would tell us that ‘we are going to detain subversives, we are going to eat at Ford. This is the collaboration between the company and the armed forces. You have to be thankful for it’. There was a bond between military government and the company… We ate in the factory’s canteen, and it wasn’t a secret that the officers were welcomed by those who provided food… This was normal. It was a brotherly welcome. (Jorge Ernesto Berguier, in Basualdo 2006: 13, my translation)

The new data on profits provides an indication of why Ford participated in state terror. In 1974 the subsidiary had reported a profit margin of -7 per cent and in 1975 it fell to -18 per cent. In 1976, by contrast, its margin rebounded to 11 per cent and in 1977 it was 10 per cent. Ford thus illustrates what a corporation will do to defend its bottom line.

References

Andersen, M.E. (1993) Dossier Secreto: Argentina’s Desaparecidos and the Myth of The ‘Dirty War’, Boulder.

Basualdo, V. (2006) ‘Complicidad patronal-militar en la última dictadura argentina’, Engranajes, special supplement, March.

CONADEP (1984) Nunca más: Informe de la comisión nacional sobre la desaparición de personas, Buenos Aires, on-line: http://www.desaparecidos.org/arg/conadep/nuncamas/nuncamas.html (accessed 20/02/15).

Castro, R.H. (1978) ‘Disappearance of Ceramics Workers in 1977’, telegram, 14th June, on-line: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB73/780614dos.pdf (accessed 20/02/15).

Ferreres, O.J., (2005) Dos siglos de economía argentina, 1810-2004: Historia argentina en cifras, Buenos Aires.

Hearn, Kelly (2006) ‘Ford’s Past in Argentina’, The Nation, on-line: http://www.thenation.com/doc/20060508/hearn (accessed 23/08/09)

Munck, G.L. (1998) Authoritarianism and Democratization: Soldiers and Workers in Argentina, 1976-1983, University Park.

Romero, L.A. (2002) A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century, University Park.

Walsh, R. (1977) ‘Carta abierta de Rodolfo Walsh a la junta militar’, on-line: http://www.desaparecidos.org/arg/victimas/walsh/carta.html (accessed 20/02/15).